The final game in the Wizardry series and the last game released by Sir-Tech Canada before they ceased operations in 2003, and having spent nearly a decade in development, it also saw the biggest overhaul the series ever had. With a 3D engine, full 360-degree movement, an overhauled stat and skill system (running to 100 rather than 3-18 like traditional D&D) and even tweaked combat that took place in the very same 3D world you were exploring rather than a separate combat screen (with environmental obstacles, formations and enemy distance becoming new factors as a result), the Elder Scrolls influence is certainly apparent. They even took a cue from the Jagged Alliance games and gave your created characters voice lines and lots of incidental dialog for battles and just exploring the world so they felt a bit more "alive" and had more personality than just their class. Some other nice touches also make the world feel more dynamic, like wandering NPCs and weather effects. Make no mistake, though, it's still very much Wizardry - turn based battles, punishing difficulty that actively encourages savescumming and lots - and I do mean lots - of experience farming, treasure looting and solving arcane puzzles are required to see the end. Tying in with the previous two games, there are also five potential starting points depending on how you finished Wizardry 7, three potential endings, and even your choices in 6 factor into how the story plays out here if you keep the same party across the whole trilogy. There's even a nice callback to the series' origins with a few hidden "retro style" dungeons with primitive wireframe graphics, 90 degree turns and teleporter and spinner traps to confuse the player. It's a shame it was the last western-developed Wizardry, as it's neat to see how one of the genre's keystones evolved over the years and what potential it would have reached had it continued. At least its legacy lives on, with new spinoff games and rereleases and a recent HD remake of the first game from Digital Eclipse.

RPG reviews from actual RPG fans, not fanboys or paid shills in the pockets of industry giants!

Saturday, August 24, 2024

Wizardry 8

Tuesday, July 23, 2024

Aidyn Chronicles: the First Mage

Aidyn Chronicles was one of the last games released for the Nintendo 64 and one of the few among its very small library of RPGs. It came out only a month after Paper Mario, though, which probably did it no favors whatsoever. Neither did its presentation, honestly - Aidyn Chronicles is quite possibly the ugliest game on the platform, and if you're familiar with the N64's library, you know that's no small feat. For its part, the gameplay is at least relatively ambitious - an open world RPG with a day-night cycle and with an array of skills reminiscent of computer RPGs like lockpicking, stealth, disarming traps, reading books, identifying items and even armor crafting and alchemy. All of these can be trained up after battle by spending experience points, which act as a spendable currency, and at certain thresholds of total points earned your experience level increases (which mostly determines what enemies will appear as you wander around). Combat operates like a more advanced version of Quest 64 with the same movement-range mechanic, though you do get party members and more options to utilize. Oh, and there's permadeath, too, so if someone dies they're gone for good. There's quite a bit going on mechanically with Aidyn Chronicles, but it's just not a lot of fun to play - the world is rather large but pretty bland, combat is frequent and rarely has much variety, and the overall story is pretty generic, with a lot of drawn-out dialog scenes and not much in the way of memorable characterization. Aidyn Chronicles might be worth a look as a relatively unique take on role playing games for the platform (and in some ways, a much more developed Quest 64), but there's not much reason to spend a lot of time with it; especially since Morrowind - a much better open world skill-driven RPG in virtually every respect - came out the following year.

Tuesday, October 4, 2022

Paper Mario

The Nintendo 64 was a platform with a serious shortage of RPGs, especially in light of it following in the footsteps of the Super Nintendo, which had so many brilliant examples of the genre that are still regarded as classics today. Nintendo had planned a new approach to Mario in the realm of RPGs, but as Squaresoft declined to work with them again in favor of developing Final Fantasy VII on the Playstation, the task instead fell to Intelligent Systems. But does this new approach to a Mario RPG have enough charm to appeal to die-hard RPG fans, or does Paper Mario fall as flat as its namesake?

The Nintendo 64 is the strange middle child of Nintendo's console lineup; choosing to stick with cartridges in an era when optical discs were fast becoming the new standard, as well as utilizing 64-bit architecture that was difficult to program for, alienated many third-party developers from working on it. Even Nintendo seemingly had misgivings about the limitations of cartridges, as they quickly made plans to develop a disk drive addon for the Nintendo 64; however, ongoing delays led to said peripheral only being released in the system's twilight days and only available via mail order in Japan, making it a significant financial and PR failure for the company. As a result of this, many games that were originally planned for the Disk Drive peripheral were either reworked to use base hardware (Kirby 64, Ocarina of Time), ported to other platforms (Dragon Quest VII), or ultimately cancelled entirely (Snatcher, Mother 3).

Paper Mario was one of many games planned for the 64DD platform, though as a result of its failure, it was reworked into a cartridge game and became one of the last major releases for the system. It was also originally developed under the title of "Super Mario RPG 2", though they later changed that as it bore little resemblance to the original Super Mario RPG in terms of design and aesthetic. Indeed, rather than the prerendered CGI style Mario RPG had used, Paper Mario draws more inspiration from western cartoons and Parappa the Rapper on the Playstation, having soft-edged 2D sprites on three-dimensional backdrops that give the game the look of a pop-up book. The game plays with this throughout as well, with characters visibly rotating and falling flat in 3D space and switches causing the scenery to dynamically shift and reassemble into new shapes - something Playstation RPGs with pre-rendered backgrounds weren't able to do, and it's quite fun to watch whenever it occurs.

Paper Mario's core gameplay is familiar if you've played Mario RPG beforehand, retaining its minigame-based elements in combat. Well-timed button presses cause your attacks to deal extra damage and reduce damage from enemy attacks, and special moves often come with unique minigames of their own - pressing the stick to the left and releasing once a bar fills, mashing the A button to fill a meter, and timed button presses. Some new elements do show themselves, though - the player can now gain an advantage in battle by landing a hit on the enemy before the fight begins, and the enemy can do the same to them, necessitating that they stay vigilant. There is also significantly less of a party dynamic here - though you get multiple sidekick characters throughout the adventure, used both in combat and to solve puzzles outside of it, only one can be active at a time. Enemies don't actively target them, either - only Mario - and if an ally takes damage they'll be incapacitated for one or more turns depending on how much 'damage' they took. SMRPG also had relatively low HP and MP totals signifying its lower-stakes, kid-friendly design, and Paper Mario takes this even further, with your basic attacks doing only one point of damage (two with a timed hit) and generally pretty low HP totals for Mario and his enemies; the absolute maximum being 99. On the other hand, this does give you a greater expectation of how your attacks can do, and even one or two points of Defense can be a serious hurdle to overcome.

Something that Paper Mario does quite well - possibly better than any other Eastern RPG before it - is giving you free reign to customize your character's abilities. Each time you gain 100 Star Points from battles, you're given the option to improve one of your three core stats - HP, FP and Badge Points. HP and FP are fairly self-explanatory, but Badge Points allow you to equip Badges that allow you to customize Mario in a wide variety of ways. Boosting your base Attack and Defense; granting all manner of new special moves that can rack up the damage (hitting all enemies at once, repeatedly attacking one enemy until you miss a timed press) or inflict status effects; using multiple items per turn at an FP cost; searching out hidden items on a particular screen; or even just changing the sound effects Mario's attacks make in combat. This affords beginners quite a few ways to give themselves an edge against tougher enemies, while more skilled players can put few levels into HP (or even none at all) and instead just focus on utilizing effective item/special move/badge loadouts to avoid damage and decimate their enemies.

Taking note of the fact that RPGs were becoming less about the main story and more about the journey you take through a virtual world, Paper Mario certainly doesn't skimp on its side content, either. There are plenty of hidden secrets to discover, side missions to complete, optional minigames to check out, and even a couple of challenging optional battles you can undertake if you really feel confident in your skills. It may not be as substantial as some of the Playstation Final Fantasies, but the amount of content Paper Mario provides is certainly nothing to sneeze at, especially for a game on the infamously space-limited Nintendo 64.

So, all told, is Paper Mario a worthy successor to Square's famous fusion of Mario's platforming and their own high-quality RPG design? Well, while it doesn't quite have the same feel and charm of Mario RPG, I still found quite a lot to like in Paper Mario. The quirky humor, creative presentation and heavy customization make it a game that appeals to both younger gamers and more seasoned ones, and Intelligent Systems - mostly known to this point for turn-based strategy games and RPGs - put their skills to good use here, making a game with familiar core design but some clever ideas that build on them in fine form. Having more visual feedback on all of your special moves is a welcome improvement as well, making some special moves that were difficult to get the feel for (Geno's Beams, spinning the D-pad for Bowser's moves, the bloody 100 Super Jumps challenge) much easier to pull off. All in all, I'd call it a fine successor, and easily the Nintendo 64's best RPG.

Developer: Intelligent Systems

Publisher: Nintendo

Platform: Nintendo 64, Wii Virtual Console, Wii U Virtual Console, Nintendo Switch Online (+ Expansion Pack)

Released: 2001, 2007, 2015, 2021

Recommended Version: All the later ports are emulations of the N64 original.

Saturday, August 27, 2022

The Bouncer

A game that had a considerable amount of hype behind it, in no small part because it would have been Square's first (published) game on the Playstation 2, but it ended up being quickly cast aside after its release. I've hyperbolically described a fair number of modern games as having the barest minimum of gameplay in between long droughts of graphical filler, but the Bouncer might just be the first game I've seen that literally follows that design philosophy. Playing like a 3D beat-em-up (and similarly to other DreamFactory developed games Tobal and Ehrgeiz), you battle 2-6 enemies in bouts that typically last under a minute and then more of the story unfolds in long sequences of FMVs, with only about three or four run-through-a-maze action segments providing any changeup between those two elements. Rinse and repeat for approximately two hours (about a third of that if you skip all the cutscenes), and you've completed a playthrough. Yes, the game is really that short; so you can imagine how many die-hard Square fans lined up, plunked down $50 to play an epic next-gen action-adventure game on their expensive new Playstation 2 console, and were left severely disappointed when they finished the whole game in the same afternoon they first booted it up. They tried to add at least some depth with the built-in experience system, where landing the finishing blow on enemies earns your character points that allow you to unlock new moves and power up your attributes, as well as a couple of extra game modes (including a four-player versus battle) where you could put your powered-up characters to a greater test, but it all just feels like fluff in the end; especially when the core gameplay is so stock that arcade games stretching all the way back to the mid-'80s already did everything it does better. Hell, even the Playstation 2 itself would get some much better RPGs that blended in beat-em-up elements like Kingdom Hearts, Yakuza and Odin Sphere, all with much more engaging and strategic gameplay to boot. So while the Bouncer might at first appear to be a long-lost Square gem to gamers who weren't around in the early 2000's, it's actually been forgotten for good reason - it's so insubstantial and over with so quickly that it leaves no lasting impact.

Developer: DreamFactory

Publisher: Squaresoft

Platform: Playstation 2

Released: 2001

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

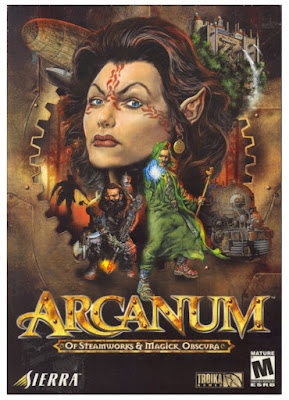

Arcanum: Of Steamworks & Magick Obscura

Publisher: Sierra On-Line

Platform: PC

Released: 2001

Recommended Version: N/A

Saturday, April 2, 2022

Tear Ring Saga: Utna Heroes Saga

After a decade at Intelligent Systems making the Fire Emblem series on the Famicom and Super Famicom, Shouzou Kaga founded an independent studio and continued to make pretty much the same style of game, just under a different title. Nintendo wasn't too happy about this, suing his company and publisher for copyright infringement and ultimately winning a 76 million yen judgment on appeal. It's easy to see why after playing it, too, as Tear Ring is pretty much old-school Fire Emblem down to the last detail, with the same style of animations, a nearly identical UI, the same degrading equipment and permadeath, and a heavy focus on character interaction and dialog (and visiting houses and shops mid-battle to resupply); the only major difference is some solid 32-bit 2D graphics and quality CD music by an ensemble cast. This one is worth a look for die-hard Shouzou Kaga fans as an unofficial sequel of sorts to the 16-bit era FE games.

Developer: Tirnanog

Publisher: Enterbrain

Released: 2001

Platforms: Playstation

Mega Man: Battle Network

Collectible card games were all the rage in the early 2000s, and it seemed like every big Japanese company was trying to cash in (even Sega got in on it with Phantasy Star Online's third episode, CARD Revolution, which was... pretty strange). Capcom took their own crack at it with the Battle Network franchise, and it proved to be quite a successful one, spawning six games, a number of spinoffs and even an offshoot series (Star Force) before being retired in 2009. The core gameplay remains essentially the same, meshing real-time action with tactics. Taking place on a 6x3 grid divided between your side and the enemy's, you get a random hand of five chips (serving as your weapons) and can pick ones that have a matching letter or type. With them, you try to clear all enemies off the board as quickly as possible, earning more chips and/or money for doing so. However, you also have to evade enemy attacks by moving around your grid, and use your chips well to ensure the enemies don't avoid your attacks and you waste your chips. Some other things can crack panels (leaving a blank space on the field that can't be crossed over temporarily) or even turn panels from one color to the other, giving you or your foe more control over the field. Pretty interesting stuff, but it ends up being a rather grindy experience; as per any collectible card game, you gradually refine and rework your deck throughout, working further toward a balance of chips that will serve you well in any scenario you face. I can see why it became such a big series in the 2000s, but like the collectible card game fad of the time, its relevance is mostly gone these days. However, its gameplay style was reworked to great effect in One Step From Eden, blending roguelike elements and numerous different characters, game modes and mods into the mix, so in an odd way, its legacy lives on.

Publisher: Capcom, Ubisoft

Released: 2001

Platforms: Game Boy Advance, Wii U (Virtual Console)

Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages/Seasons

The Oracle Games were rather odd beasts, being developed by an outside studio and released on the Game Boy Color in the months leading up to the Game Boy Advance's release. The concepts were relatively novel, too - Ages has you hopping between past and present similar to Ocarina of Time, while Seasons has you cycling between the four seasons to reach new areas and solve various puzzles. That's all good, and they're built on the same engine as Link's Awakening DX, so fans of that game will be right at home here. Unfortunately, a lot of the change-ups here aren't really for the better - many familiar items are recycled but used in strange new ways with little explanation (being able to pick up and throw enemies with the power bracelet, for example), which can lead to a lot of unclear puzzles and frustration. Animal friends are used to reach new areas and clear paths, though their controls and collision detection are frequently awkward. Bosses also don't feel well-designed a lot of the time, either having weird hit detection or requiring spot-on timing to overcome, and I generally just found them annoying to fight. The ideas here are interesting, but the execution is a bit lacking; I can't help but wonder if they just needed a bit more playtesting before their debut, but regardless, I don't rank them among the Zelda franchise's best. Give them a look, but try before you buy.

Developer: Capcom/Flagship

Publisher: Nintendo

Released: 2001

Platforms: Game Boy Color, Nintendo 3DS (Virtual Console)

Thursday, May 27, 2021

Breath of Fire IV

The fourth Breath of Fire game and the second on the Playstation 1 was released at a time when the platform was being largely phased out in favor of its successor and thus it went largely ignored by critics and audiences. But does Breath of Fire IV prove to be a worthy RPG despite its low-key release, or is this just a lackluster last hurrah for the series on the Playstation 1?

The overall design of the game has been much refined too; evident right away in the presentation and cinematography. Right from the word go, Breath of Fire IV opts for a more movie-like feel with dynamic camera angles and staging and a greater focus on characterization and worldbuilding while relying far less on corny humor. The pacing is vastly improved, with dungeons feeling focused and loading being virtually unnoticeable, especially in combat. Minigames are well-integrated into the narrative, and while still not amazing, are fun little diversions rather than irritating chores standing in your path. Most mundane NPCs in the game have portraits in dialog, which is quite a nice touch, and the solid animation of 3 is even better here, with fluidly-animated sprites and a surprisingly good framerate in the thick of battle (though you can hit occasional slowdown while wandering towns and dungeons). Even the movement is tighter now - you still move on a set graph and it uses the same isometric style, but I didn't find myself struggling to position myself in front of a switch or sign nearly as much. Hell, you even have the option to offset D-pad presses to move in diagonal directions if you wish, which is very nice (though I didn't end up using this). Even the fishing minigame has seen some upgrades, adding some free-roaming around the fishing spots to find the best places and even letting you reel fish in easier by timing button presses to the drums in the music. Hell, if you happen to own a Playstation 1 fishing controller, it is fully supported by Breath of Fire IV, showing that they really did go the extra mile in every way they could.

Town and dungeon design is much tighter this time too, with small, focused maps instead of huge sprawling ones, and nearly all the dungeons being built around puzzles rather than static, empty corridors full of monsters. They went slightly overboard with the "packed-in" feel, though, as the halls and corridors you traverse are very narrow and, paired with the isometric perspective, you'll have to frequently rotate the camera to see where you are and where you have to go. They did attempt to offset this somewhat with Nina's action command, though - she floats up into the air and looks down on the area from above, which can help you get your bearings at times.

Of course, they do add some new twists onto the game too. Combat has been overhauled substantially - not just in pacing, but mechanically too. You get a party of six with a maximum of three active in combat at a time, but all of them are with you at a time - no exiting to the map to swap characters when the plot dictates. One can even switch characters in and out of the active party mid-fight, with those on the sidelines slowly regenerating AP each turn, and while they're sitting out they're also burning turns of status effect duration; quite handy as you can imagine. Switching characters to deal with particular foes is important too, as each character now has an elemental affinity - they're usually given spells of that element to cast, take less damage from it and more from an opposing element. Characters don't ever really become obsolete, either; unlike 3, attack magic isn't rendered useless by poor scaling, and particularly powerful skills (like Ryu's dragon morphs) are toned down considerably here.

Another major factor in combat is the new combo system. Essentially, what this does is let the player chain together skills and spells to not just deal more damage (growing higher as the combo count rises), but to create entirely new attacks. Elemental spells, cast in proper order (Fire -> Wind -> Water -> Earth -> Fire) will create bigger and more powerful attacks, and some other, less conventional options exist, like combining a healing spell with a fire-element attack to create one heavily damaging to undead enemies. Even status-inflicting abilities play into this; useless in most RPGs, here they score two hits - one dealing light damage and the other having a chance to inflict the effect. The latter hit can also combo with other attacks, giving them another chance to inflict that status on top of their normal effect. There are a ton of possibilities with this new element, which makes combat more engaging than in any prior BoF game - every time you get a new skill you'll find yourself experimenting with it, seeing what you can combo it together with and trying to work towards the damage and combo chain goals that some Masters require. A big achilles heel of older RPGs is the stale, repetitious combat, but Breath of Fire finally crawled out of that hole with IV and made battles something I looked forward to rather than started to groan at.

Breath of Fire IV doesn't break a lot of new ground; in fact, in terms of overall design it's remarkably similar to 3. However, it also stands as proof that polish can make all the difference between an arduous RPG experience and a solid game. The cinematography, dungeon designs, pacing and writing are all a massive improvement on 3's, creating a compelling and epic adventure that plays great to boot. The game looks gorgeous, with visuals that manage to hold their own against even the almighty Square even with the much smaller budget; beautifully realized and expressive character designs, smooth combat animations, and creative, sharply rendered environments and visual effects. The music, as in any good RPG, carries the mood perfectly, creating an experience that's often grim and depressing, but also very compelling. Breath of Fire IV is easily the most impressive BoF on a technical level and in terms of storytelling, and is certainly worth a look for any serious fan of RPGs.

Developer: Capcom

Publisher: Capcom

Platform: Playstation 1, PlayStation Network

Released: 2001

Recommended Version: The PSN version is a direct port of the PS1.

Monday, June 1, 2020

Saiyuki: Journey West

Koei is mostly known in the west for two things - incredibly deep strategy-simulation games like Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Gemfire and Liberty or Death, and of course the Dynasty Warriors franchise - over-the-top beat-em-ups based on wars in ancient China that have also been licensed out to just about every popular media franchise there is. Both are niche games and often attract controversy for having relatively few significant changes between entries, but they nonetheless remain strong sellers and show no sign of stopping anytime soon.

Less known about them, however, is that they actually have a fairly sizable presence in the RPG world. Probably their best known division in the west is Gust, known for creating the Atelier series, a franchise which places heavy emphasis on item crafting. However, their presence in the genre goes back much further - all the way back to their founding in 1978, where they published obscure games for Japanese computers like The Dragon & Princess. They also produced the Uncharted Waters games on various platforms in the 90s, which have gone on to become cult classics.

Before Gust became a prominent name, though, Koei tried out a few other attempts at role-playing games in the west, none of which really caught on. Saiyuki: Journey West was one of those, seemingly built to cash on on the craze of anime-influenced turn-based strategy RPGs like Final Fantasy Tactics and Ogre Battle, but it never quite caught on, probably in no small part due to being released in 2001 - a time when the Playstation 2, Gamecube and XBox were all freshly released and making waves across the world.

The few that did play it, though, found a pretty solid game. While not quite as in-depth as others in the genre, nor as highly-produced as games like Final Fantasy, it provided a solid turn-based experience that was easy to pick up and play, yet surprisingly challenging to master. Based on the classic Chinese tale "Journey to the West", though of course creative liberties are taken in the name of gameplay and story.

One significant example of this is in the game's playable characters. Each of the playable cast is aligned with one of the five Chinese elements - Fire, Water, Earth, Gold (Metal) and Life (Wood), getting bonuses when utilizing or resisting spells of their particular element and worse effects with the opposing element. Many of the characters utilize their trademark abilities from the story - Son Goku can utilize a cloud to get more movement range in a turn, for example.

Every character except Sanzo also has a "Were" ability, essentially letting them transform into a huge, powerful beast for a limited time and unlocking the majority of their special abilities. They do tend to be overwhelmingly powerful (having hundreds more HP than the characters' base form), but to make up for this, they are also very limited for much of the game. All of these are tied to a "Were meter" on the screen that is depleted each time a Were character utilizes a specific move - simply transforming into one takes one pip, a normal attack takes one, while some special attacks can take multiple pips at once. Once the gauge empties, all Were-form characters immediately revert to their base forms. The bar itself can be leveled up through battles, earning more experience and levels (and therefore pips) the quicker a player clears battles. It's a surprisingly well-integrated mechanic, too - most battles in the game are very difficult without well-placed special moves by one or two Wered characters, so balancing their use and clearing boards quickly is key to long-term success.

Sanzo himself has no such ability, though, and for a significant portion of the early game isn't really able to do much in comparison - just use a heal attack or deal mediocre damage with his staff, and you only really want to do the latter in a pinch as his defeat means an instant game over. However, he does come into his own after some time; his high Magic stat makes him an effective caster once you start finding scrolls to cast from, and as the story progresses he will acquire "Guardians", summonable allies that will grant benefits to the entire party for a few turns and Sanzo a special, 0-MP spell for the duration. For example, summoning Mother will grant the entire party HP regeneration for a few turns, while calling Fool will boost their attack power and grant Senzo the 0-MP FlameWhip attack. Each new Guardian acquired will also bolster the innate Attack stat of his staff - important as his weapon is the only one that cannot be improved at a blacksmith.

Because of the game's linear setup, it can be tricky to manage one's party and keep them all up to speed, making some later battles very difficult if not impossible to overcome if you simply truck on. For this reason, it's often a good idea to visit Dojos, where the party can train to power up without restriction. Extra money can be earned by taking on sidequests at the "Post", and if you're in more of a gambling mood, one can play an optional card game (simply referred to as "Card Game") to earn some rare prizes - usually in the form of equipment that can't be gotten elsewhere. The game itself plays similarly to the traditional Japanese card game Oicho-Kabu, so reading up on that will prove beneficial if it's something you plan to spend any amount of time on.

Looking up forgotten RPGs from yesteryear is always a gamble; whether it's forgotten for good reason or simply an overlooked gem is something you can only truly find out by playing it yourself, and that's sometimes an expensive endeavor. That said, I found Saiyuki: Journey West to be a surprisingly good time. It's not the PS1's most immaculately-produced RPG and its late release ensured that not too many people would play it even if it was, but it's a solidly-made and entertaining game for strategy RPG fans. It is somewhat hard to come by these days in physical form, but is available as a downloadable title on the Playstation Network (playable on Vita, PSP and PS3), so those who only have a few bucks to spare can give it a try too.

Developer: Koei

Publisher: Koei

Platform: Playstation 1, Playstation Network

Released: 2001, 2011

Recommended Version: The PSN port is a direct emulation of the original game.

Monday, November 18, 2019

Wizardry: Tale of the Forsaken Land

Wizardry is a quintessential early computer RPG franchise - one of the very first to emulate Dungeons and Dragons in format and design, as well as the first to feature color graphics and a party-based experience. While it would soon be outshone by games like Ultima and the Gold Box series (mostly because its engine and graphcis started to look very dated in comparison), the franchise still trucked on for over a decade, getting its final entry in 2001 with Wizardry 8. Sir-Tech's last surviving branch dissolved not long thereafter, though, and the franchise mostly came to an end in the west.

However, Wizardry found a very different life in Japan, with numerous spinoff games coming into existence under a variety of companies as late as 2017, very few of which were ever localized for the rest of the world. Tale of the Forsaken Land is one of the few that was, released in 2001 by then-niche RPG publisher Atlus and developed by Racjin, a fairly unknown company that has a few cult classics to their name (probably the best-known being the Snowboard Kids games for the Nintendo 64).

From a quick glance, though, it's plain to see that the feel of the Wizardry franchise was kept alive for Tale of the Forsaken Land. As in most of the western games, the game is primarily centered on a single dungeon, there is a hub-town that one interacts with via menus, it takes place in a first-person perspective (albeit now with 3d graphics for enemies and the dungeon itself), and even the familiar character creation elements return - the same classes, stat requirements and alignments come back once more. Basically, if you played any version of the first few Wizardry titles, you'll feel right at home here.

Other iconic elements of the franchise quickly show themselves too. Leveling up only occurs "between adventures", IE in town, so you'll probably want to make frequent trips back to rest and power up before getting too far in. Spells are broken up into distinct levels, which each get their own number of castings between rests, so you'll want to save them for when you're in particularly tough battles. Enemies often appear in large groups, and like your own, have a front and back row, with the latter largely being out of reach unless you have ranged weapons or spells to attack them (or clear the front row first). Enemies will often kill a character in only a few hits, making upgrading armor and shields frequently to get more defense and evasion a key part of strategy. One can also freely change classes between ones they have the stats and alignment requirements for, with a few more powerful ones (Ninja, Samurai and Knight) having particularly high requirements, but a strong combination of abilities. And of course, a big part of the game is finding unidentified items that may be magical or otherwise rare/expensive, taking them back to the shop for appraisal, and then selling or equipping them accordingly. They seem to spawn randomly on any given floor, too, so retreading dungeon floors in search of more loot is often a worthwhile endeavor.

Tale of the Forsaken Land does quickly take steps to make itself distinct, though. Technology for those old floppy disk based games didn't allow for a huge amount of storytelling within the game itself, but being a PS2 game, that's obviously not a problem anymore. To that end, there is a running storyline throughout Tale of the Forsaken Land, with a lot of characters to meet and recruit and side-quests to undertake along the way (often going hand-in-hand with one another). In addition to joining you for quests, characters do have distinct personality traits, and staying on their good side is often necessary to keep them in the party; some will get angry with you if you battle friendly enemies, for example, while others hate particular enemy types and will like you more if you kill a lot of them. This also quickly ties into a major mechanic called "Allied Actions", which are parties your group can collectively take once their trust in each other is high enough. These include things like Double Slash (two allies attack a single enemy in tandem, getting a bonus to accuracy and damage), Hold Attack (one character immobilizes an enemy while the other hits them - great for enemies with high evasion) or Warp Attack (removes the entire front row from the fight for a turn, causing any attacks targeted at them to miss). A lot of these aren't particularly great, but some prove to be extremely powerful and are well worth getting.

Something else new is the spell crafting system, which is a bit of an odd beast but adds quite a lot of depth to the game. One can find stones within the dungeon that teach spells or, if they already have that spell, upgrade it to make it more effective. Enemies frequently drop items that can be used in their own right to recover HP, cure status effects or deal damage, but oftentimes these can be taken back to the shop in town to craft new spell stones or Vellums. Vellums are essentially rarer and more powerful spells, often requiring you to find a recipe and then craft them from three (often rare) components. They tend to be quite useful, though, so it's often worth the effort it takes to track them down. If you're finding a lot of a particular stone, you can also disassemble it back into its base components to craft something else if you wish, so this does end up being a pretty big component of the game's strategy in the long run.

Some elements of the game's design are also relatively strange for first person dungeon crawlers of this type. One thing that surprised me is that encounters are actually visible in the dungeon - enemies appear as a hazy outline that you can evade or outmaneuver if you don't wish to fight at that time. I was somewhat surprised to find that opening chests isn't solely for the thief class, either, instead being governed by a minigame where you have a few seconds to push a sequence of buttons; in fact, I started the game as a Cleric and got a personality trait related to successfully unlocking chests, which felt a little bizarre for a D&D-like. Thieves do still play an important role in disarming traps, though, so you'll still want to have one (or a Ninja) around for that purpose.

For an early PS2 game running off a CD, TotFL has quite a distinct aesthetic too. While the dungeons and enemies are in 3D, the game does make use of detailed 2D sprites for story characters and cutscenes, and they all work well with the game's dark setting and overall bleak mood. Music fits in with this too, keeping the atmosphere dark and foreboding, yet urging you to move on to uncover the story's mysteries. The translation in the game is somewhat clunky, but it works well enough to keep the game moving and never becomes distracting, so I didn't mind it too much.

So, does Tale of the Forsaken Land live up to the legacy of the Wizardry series? I certainly think so. It maintains the challenge and dungeon-oriented elements of the franchise while working in some components of Japanese RPGs as well, emphasizing characters and storytelling as a key part of the experience. Both components are balanced quite well, presenting a game with a lot of depth and challenge and a good narrative to keep the player motivated even when it can be frustrating to make progress at times. It may not be the Playstation 2's most highly-regarded RPG, but I certainly think it's one worth a look for any serious fan of old-school dungeon crawls.

Released: 2001

Platform: Playstation 2

Recommended Version: N/A

Sunday, June 3, 2018

Jade Cocoon 2

Well, the fact that there has not been a Jade Cocoon 3, nor any attempt by Genki to revisit the monster breeder RPG genre, probably answers that opening question for you. But let's take a closer look at the game and see exactly where this franchise met its downfall.

One of the first things the player is bound to notice is that the overall aesthetic of the game bears almost no resemblance to the original. Katsuya Kondo is no longer in the role of character designer or animation director, resulting in a drastic aesthetic overhaul. The setting of the game is no longer that of a lush, natural environment, but now has the player hopping between dimensions, going from one surreal alien locale to the next. The tone of the original game is lost as well - Jade Cocoon 2 takes on a much more irreverent, almost campy feel to its narrative, with silly story elements, over-the-top acting and outlandish character redesigns at every turn. Many characters return from the first game, though they bear little resemblance to their old counterparts; even Levant, the protagonist of Jade Cocoon, returns as what I can only describe as a "space hippie", sporting an exaggerated colorful outfit, a yin-yang pendant, an enormous purple lute and mile-long hair bangs. While never atrociously annoying, and some elements of this can be amusing - Nico's irreverent narration of the storyline easily being the highlight - it's a very stark contrast to the heavy, somber mood of the first Jade Cocoon game.

Secondly, the overall style of gameplay is heavily overhauled from the first Jade Cocoon. Instead of an RPG with pre-rendered backgrounds and linear progression, Jade Cocoon 2 is overhauled into more of a dungeon crawler. The player travels about lengthy dungeons, entering rooms in search of a spore pod which will allow them access to the next floor. Said rooms can also contain random items, monsters or trainers - either mundane ones who provide a modest fight or "Rivals" who provide much more of a challenge. Defeating other trainers earn you medals, which in turn unlock new challenges that can grant the player rare monster eggs.

Jade Cocoon 2 also has a more generic and utilitarian RPG setup overall, with the player being encouraged to undertake a number of fetch quests and defeat-the-monster challenges. These in turn grant a variety of rewards, such as rare items or monster eggs, and all will boost the player's Reputation, certain levels of which are required to take advancement exams in order to be able to unlock and use more monsters simultaneously in battle.

Which leads us to Jade Cocoon's most distinct difference: its combat system. While the first game was a standard turn-based affair not dissimilar to its main inspiration of Pokemon, Jade Cocoon 2 takes things in a far different direction, attempting to add more of a strategic bent. In essence, combat now operates with both participants having a 3x3 grid, with the protagonist and his rival in the center space and the surrounding spaces populated by up to eight monsters. The row facing the opponent is the one that deals out attacks and takes damage whenever the player takes their turn, and the shoulder buttons rotate the grid to face a different set of up to three monsters toward the opponent.

What determines the winner of a fight is not so much the monsters themselves, however, but taking care to balance attacking, defense, and not leave the player character open to attack. If the center space on the row facing the opponent is vacant, the opponent can then attack the other character directly, depleting one of their Shields; once all of their Shields are depleted, the fight ends immediately. Thus, a significant part of strategy in combat is rotating one's monsters at the right times to tank opponents' attacks, heal their group of monsters, or go on the offensive. Placing one's monsters strategically is important as well - each side of the grid is aligned with one of four elements (Earth, Wind, Water and Fire) and placing monsters that match that alignment will grant a bonus to their attacks and abilities. Monsters cannot be placed in the center space of the grid that opposes their particular element, and they will always use an attack correlating to the element of that side of the grid if they have one. Essentially, it combines elements of Ogre Battle into the formula of the first Jade Cocoon and ends up being a much more complex experience on the whole.

What it all boils down to is that Jade Cocoon 2's big failing wasn't being a bad game; it's a competently designed experience in almost every respect with some interesting mechanics and an enjoyably strange atmosphere. The problem was that it made the same mistake Chrono Cross did only a year prior, billing itself as a direct sequel despite bearing little resemblance to the first game in terms of direction, and in fact actively going out of its way to upend many established elements of the first game's lore and characterizations. Its irreverent tone, heavier emphasis on mundane quests and dungeon crawling, and a larger random element all contribute to it being a much different experience than the original. Those that were drawn in by the first game's appeal as an interesting Pokemon alternative felt left out, and the overall design and atmosphere was too bizarre to draw in fans of older and more traditional RPGs, or even ones who jumped on the bandwagon with recent hits like Final Fantasy VII that sold themselves on having a heavier tone and more adult themes. Basically, it simply failed to find much of an audience, selling about 100,000 copies to its predecessor's 270,000, and in an industry driven by revenue, that's the worst sin a franchise can commit in a publisher's eyes.

Developer: Genki

Publisher: Ubisoft

Platform: Playstation 2

Released: 2001

Recommended version: N/A

Thursday, August 24, 2017

Shadow Hearts

Sacnoth is a fairly obscure company to many despite having a relatively big name attached to it; Hiroki Kakuta, composer for Secret of Mana and Seiken Densetsu 3, was one of the company's founders and helped to write, compose and design their first mainstream game with funding from SNK. The end result was Koudelka, a game which, while praised for its high-quality cutscenes, drew much criticism for its poor balance, clumsy combat system and unimpressive music (particularly given Kakuta's previous works). This, paired with internal strife over the game's direction and SNK's financial troubles putting the company's future in doubt, caused Kakuta to depart the company shortly after Koudelka's release.

SNK's IPs were shortly thereafter bought out by Aruze (mostly known for creating pachinko/slot machines) and Sacnoth (later renamed Nautlius) was allowed to continue developing games. Their best-known work was the Shadow Hearts franchise, which more or less served as a followup to Koudelka with its dark themes and a unique setting of an early 1900s Earth where magic, demons and monsters were the norm. Its cast of characters was equally colorful, working several real-life events and people into its stories (though obviously in a fictionalized form) while also utilizing elements popularized in many early PS1 RPGs, such as minigame-driven action and prerendered CGI backgrounds for dungeons.

Shadow Hearts' most defining element is its "Judgement Ring", which factors heavily into almost every aspect of the game and serves as its overarching risk-versus-reward mechanic. Essentially it's a timing-based minigame, tasking the player to watch indicator sweeps around the ring and time a press of the X button when it lines up with colored areas on it. In combat, everything from basic attacks to using items utilizes this, though in slightly different ways. Status-curing items often simply require a press on a single lit area, while items and normal attacks can get a slight bonus to their effects by timing the button press to a narrow red sliver at the edge of a hit area. Normal attacks can hit up to three times (with each hit zone having a red zone for bonus damage); special moves, on the other hand, often have several areas to hit - one or more green areas before the attack zone, then a hit zone to actually carry it out. There are even a few instances of the Judgement Ring appearing outside of combat, such as having to open a lock or search an area, find an item, or play the "lottery" for a chance to win rare and powerful items (though one must also find relatively scarce Lottery Tickets for the chance to do that).

Further following up on this, there are several enemy status effects that can affect the ring, such as making it sweep faster, making the indicator invisible, or shrinking the ring to make it harder to see and time one's button presses. However, the player can utilize this to their advantage, with accessories that affect it in various ways. A few of these include making the indicator invisible, but doubling that character's attack damage, giving them a massive speed boost at the cost of making the indicator sweep twice as fast, or a plethora of items that can allow the indicator to sweep around the ring multiple times per turn, effectively allowing them three or even five attack sets in one round. While all of these carry substantial risk (as one miss will cause the whole attack string to abort per usual), they can be absolutely devastating when used well. One can also make slight tweaks to their weapons through "acupuncture" in order to slightly expand the hit area on their character's attacks or do slightly more damage at the cost of making the hit areas slightly smaller, but as this tends to be very expensive it's generally best saved for near the end of the game, when the ultimate weapons start to become available and money is much less of a concern.

Another unique element of the game is the Sanity meter. Each character has a set amount of "Sanity", and over the course of battles, it will deplete at the rate of one point per turn. Once it reaches zero, the character will go "berserk" and will begin randomly attacking allies and enemies alike each turn until their sanity is restored or the fight ends. While not as big of a factor as the Judgement Ring (as fights can generally be ended long before it ever becomes a problem), it can be a concern during boss fights, particularly with characters who have a very low amount to start. It can also be factored into the game's risk-versus-reward elements, with things like an accessory that give a substantial stat bonus but cause Sanity to deplete twice as fast, or enemies that can forcibly deplete a character's sanity, putting the player at greater risk of losing control over them.

The characters in the game , while they have distinct personalities and some rather humorous dialog most of the game, are sadly rather generic on a gameplay front. For the most part, they're generally themed around a single element and fill a single niche within the party (the healer, magic user, fighter, etc) with little opportunity to expand beyond that role. Probably the most amusing of these is Margarete, a a fictionalized version of Mata Hari who utilizes gadgets like grenades, bazookas and airstrikes (all called in with a cellular phone) to do battle.

By far the most versatile character of the bunch is the main character, Yuri. His defining feature is his power as a Harmonixer, which allows him to transform into various demons to do battle, each with their own elemental affinities and skill sets. New forms are unlocked via defeating enemies to earn points toward one of the six elements (fire, water, wind, earth, light and darkness) and then traveling to the "Graveyard" via any save point and defeating a demon in battle once they have enough; once that demon is defeated, Yuri can then morph into it and use its skills himself. However, this does comes at a price - defeated enemies will slowly cause the Malice gauge to build, and when it is full, random encounters may occasionally be replaced by a fight against a rather difficult miniboss. In order to prevent this happening, the player must make occasional trips to the Graveyard and fight a phantom enemy in order to dispel the malice temporarily.

Fittingly for a survival horror inspired title, Shadow Hearts basks in its dark themes and imagery. Themes of wicked sorcery and supernatural evil are prevalent throughout and some of the enemy designs are grotesque and downright bizarre; dogs with zombified arms emerging from their mouths, zombies, ghosts and demonic entities of many denominations to name just a few. Areas in the game are equally grotesque and unsettling, with the first playable segment of the game famously being a train with nearly everyone on board having been messily slain by the game's villain and the player's adventures leading them to places like a village of cannibals and an abandoned mental asylum used for dark experiments. Some of the puzzles are seemingly a nod to this as well, with the player having to find various themed keys and clues that read like something from a Resident Evil game. This is all accompanied by moody soundtrack that complements the unsettling nature of the settings while lending a distinct feel to each of the game's environments.

But while the game certainly looks good and sounds amazing (in no small part due to the contributions of Yasunori Mitsuda and Yoshitaka Hirota), it does show some trouble with what was a relatively new element of gaming at the time: voiceover. While Midway did go to the trouble of getting professional actors for the roles, there are overall relatively few voiced scenes in the game (and the few that are tend to come across as underdirected and campy). There is some noticeable corner-cutting in the combat aspect of the game as well, with characters frequently jumping back and forth between Japanese and English voice tracks during their special moves (particularly Margarete, whose English and Japanse voices are often heard seconds apart within the same special attack animation). It's certainly not a deal-breaker, but given the high production values of the rest of the game, it is a bit jarring to hear at times.

Shadow Hearts also suffers from a few dated design elements; random encounters are still prevalent throughout (though thankfully are on a relatively long timer, particularly compared to other contemporary RPGs) and some combat animations tend to drag on, particularly later in the game. There is some lackluster balance at times, with some bosses being almost laughably easy and others requiring either very specific strategies to defeat or simply brute-force grinding. Character balance leaves much to be desired as well, with some characters being overwhelmingly powerful and others being far more limited and virtually useless. There are some easily missed plot flags as well, with the player able to miss out on at least one ultimate weapon and even the good ending because of easily-overlooked, innocuous things such as not examining a gravestone or talking to a specific NPC (with no indication, dialog or otherwise, that these things are critical to achieving these elements). Characters do not gain any form of experience when they are not a part of the active party either, which can result in some (particularly Yuri) being many levels ahead of the rest by the end of the game.

Despite a few small faults, however, Shadow Hearts is a very competent game. Its risk-versus-reward centered gameplay, eerie atmosphere and colorful cast of characters make it an engaging title to play, and its unique urban fantasy setting certainly makes it interesting from a storytelling and visual perspective. It isn't a perfect experience by any means, but it is worth a look as a decent alternative to the big name RPGs of the era.

Developer: Sacnoth

Publisher: Aruze, Midway

Platform: Playstation 2

Released: 2001, 2002

Recommended version: N/A